Seven years ago, Sophie Howe became the world’s first ever future generations commissioner. Tasked to be the guardian of the interests of future generations in Wales, she was made responsible for giving advice on long-term thinking to the Welsh government – including on climate.

It’s a role that at once both makes sense and raises a host of difficult questions. How on Earth can someone manage to represent people who will be born in five, 50 or 100 years, for example? “I always say that I sort of represent the unborn but they don’t talk to me very often,” says Howe. “It’s impossible for us to know exactly what future generations are going to need.”

That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try, however. As climate impacts begin to bite, and are only set to get worse as time goes on, governments, societies, philosophers and young people are finding themselves tasked more and more to consider how the wellbeing of the billions of people who will live in the future can be accounted for in decisions today.

Wherever I go anywhere in the world and I talk about the future generations act, the general response is, ‘Oh, my God, like, why doesn’t every country have one?’ – Sophie Howe

It turns out there are many different ways to bring the influence of our descendants into present-day climate action, from new approaches to legal cases and citizen assemblies to future generations commissioners like Howe, and revisiting traditional ways of thinking for the long-term.

A commissioner for your great-great-great-grandchildren

Climate change and the intergenerational issues around it are of course just one part of a much larger picture of long-term risks that face the world, from the threat of nuclear war to technological risks associated with artificial intelligence or biological weapons to long-lasting social issues such as racial injustice, says Roman Krznaric, a philosopher and author of The Good Ancestor.

However, “the one thing we know about the climate crisis is that it has incredibly long-term impacts”, he says. “That’s the core of the intergenerational climate problem: we’ve colonised the future, we treat it as a dumping ground for ecological degradation, and technological risks, as if there was nobody there.”

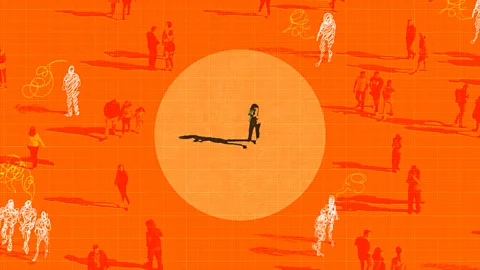

We also know that billions upon billions of people will inhabit the future, “even though they have no political voice, no political representation”, he says. “Our politics hasn’t been designed to give those generations who will be impacted by our climate actions any kind of voice in the system.”

The wellbeing of future generations act passed in 2015 by the Welsh government (a devolved administration within the UK) is one effort to address this.

The act puts into statute a requirement for all public bodies – from health boards and local authorities to the Welsh government itself – to demonstrate how their decisions are meeting today’s needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!